The latest State of the Environment (SOE) report has just been released by the Federal Government. The previous, 5 yearly report was put out in 2016. With the exception of the urban environment (which has remained neutral) every other category, upon which the report is based, has deteriorated since the 2016 findings. The report itself is a holistic process which is designed to provide a comprehensive assessment regarding the health of the environment. It looks to analyse how things are tracking based on the available evidence while taking into account both traditional and local knowledge.

While this latest report is not necessarily uplifting, it does allows us to map trajectories over time to assist in making decisions to mitigate negative environmental impacts. For instance, previous reports tended to allude to ‘future’ scenarios as a result of a changing climate – now the report is able draw from real time issues that clearly demonstrate a link to changing climatic patterns as the key driver.

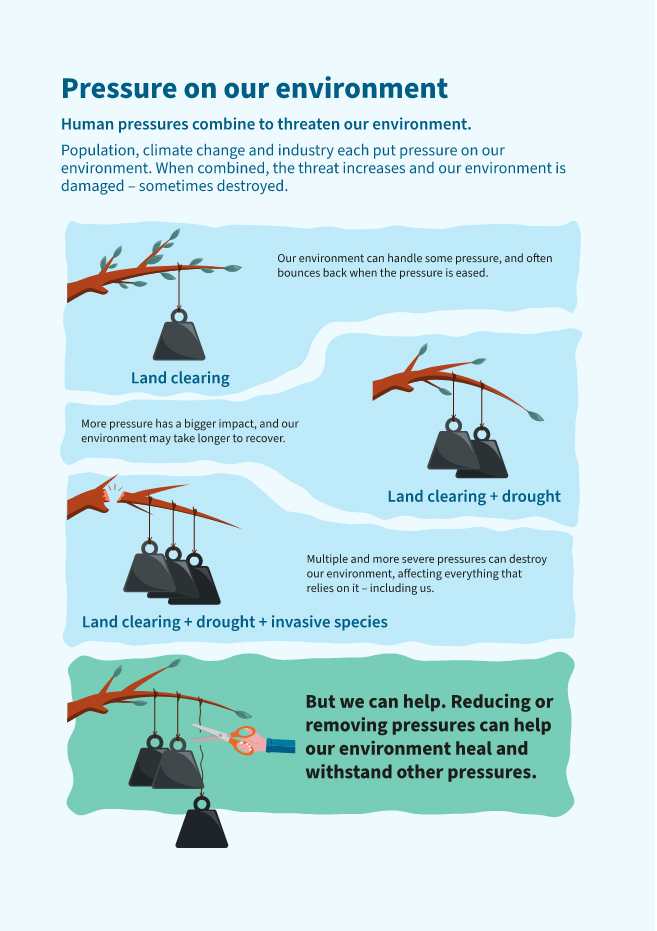

This is perhaps one of the key differences between this and the previous SOE report. Now we’re able to see the impact of what a changing climate means for Australia and are able to quantify what that damage actually looks like. Individual threats are, by nature, not ideal but their accumulation can push specific pressures beyond a tipping point. This is where we need to pay particular attention to those pressures that we can help alleviate and ease with a view to giving the environment space to adapt and heal.

“Pressure on our environment” (2021) Retrieved from https://soe.dcceew.gov.au/overview/pressures/cumulative-pressures

The data is confronting:

- Australia has lost more mammalian species than any other continent

- More than 6.1 million hectares of mature forest have been cleared since 1990

- Climate – poor and deteriorating

- Extreme events - poor and deteriorating

- Land and soil - poor and deteriorating

- Inland water - poor and deteriorating

- Coasts - poor and deteriorating

- Marine - good and deteriorating

- Air - very good and deteriorating

- Urban – good and neutral

- Antarctica - good and deteriorating

While there are significant human induced pressures – people can also assist to improve the trajectory of the environment, starting at a local level on their own properties. Helping alleviate some of the pressures by extension means the environment is better positioned to cope with the speed at which change is happening. The challenge is often the speed at which the environmental pressures emerge and take root across the country and our ability to mount a suitable response to these in a timeframe that works.

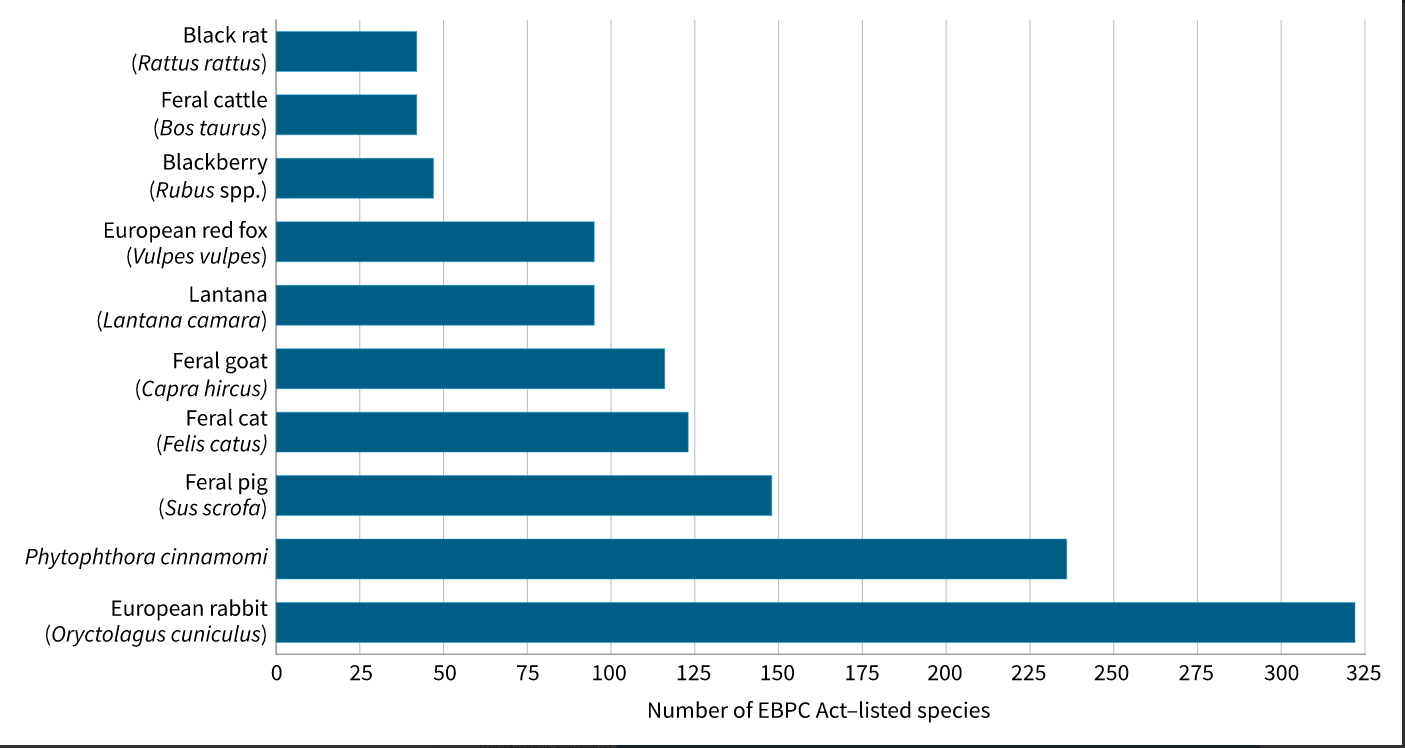

The 10 invasive species listed as affecting the greatest number of EPBC Act–listed threatened taxa

Kearney SG, Carwardine J, Reside AE, Fisher DO, Maron M, Doherty TS, Legge S, Silcock J, Woinarski JCZ, Garnett ST, Wintle BA & Watson JEM (2018b). The threats to Australia’s imperilled species and implications for a national conservation response. Pacific Conservation Biology 25(3):231–244.

Of all the current EPBC listed species in Australia the above image demonstrates which invasive species are most represented in recovery actions as threats. A coordinated response to the myriad of threats threatened species are experiencing is required if we hope to help alleviate the pressures the environment is under. It is worth noting that native species, in the wrong context, can also create significant pressure on threatened species as, for example, eastern long-billed corellas exert pressure on the ability of black-cockatoos to breed by outcompeting them for suitable nesting hollows.

It is helpful to be mindful where this information regarding the threats to the environment comes from. The State of the Environment Report reflects Australia as a whole and data to inform this is rolled up from around the country. The original paper upon which the above content is based highlights key groupings of threats to the environment. After invasive species – ecosystem modification and agricultural activities are the next two greatest threats to threatened species. Given the degree of fragmentation in the Wheatbelt it could reasonably be argued that both ecosystem modification and agricultural activities pose the greatest risk to threatened species in the Avon River Basin.

All is not entirely lost. Many local Wheatbelt landholders are actively assisting the environment of the Avon River Basin through their NRM projects, including Charlie Newman and Chelsea McDonald.

Charlie Newman, a landholder east of Newdegate, has been fencing remnant bushland and revegetating areas of the family farm for years now and has recently come on board to participate in our ‘Where the Wild Things Are Project’. As part of this he’s erected 3.4km of stock proof fencing, protecting 36 hectares of Eucalypt Woodland of the Western Australian Wheatbelt TEC from the impacts of grazing as well as having just finished 7 hectares of revegetation to improve the condition and extent of some of this TEC that was impacted by flooding a few years ago. He’s also conducting a feral animal control program across his properties which is estimated to protect 160 hectares from the impacts of vertebrate pests. Charlie is lucky enough to host Carnaby’s black-cockatoo nesting pairs on his property and has installed 6 nesting tubes with another 2 to be installed ahead of this breeding season.

Chelsea McDonald owns a 65 ha property in Nembudding (in the Wyalkatchem shire), where her aim was to revegetate the entire property and create a safe place for native species. Chelsea came on board our ‘Where the Wild Things Are’ (WWTA) project in 2021 and has since been actively progressing towards her aim.

With 46% of the property being remnant vegetation, Chelsea started revegetating the property back in 2009 and completed another 40 ha of infill and bare land revegetation under our WWTA project earlier this month. Since planting more native species, Chelsea sees noticeably more birds on the property, and species they didn’t see before the revegetation took place. Some of the birds they see now include the little button quail, a wedge-tailed eagle, Australian hobbies, kestrels, mudlarks, butcher birds, 28s, corellas, red-tailed black cockatoos, crows, galahs, willy wagtails, black-faced cuckoo-shrikes, robins, grey fantails, crested pigeons, budgies and wrens. The remaining Eucalypt Woodlands of the WA Wheatbelt on the property is also home to the endangered Shield-backed Trapdoor Spider.

Within her project, Chelsea is also controlling weeds, completing fox and rabbit baiting, cage trapping, as well as monitoring rabbit numbers. She has also installed 2 bat nest boxes.

Chelsea’s project shows that even on a small scale, making changes like adding native species back into an area and controlling feral animals does have an impact on the biodiversity of the area, and can create more habitat for species across a fragmented landscape.

If you’d like to find out more about the opportunities we can provide to assist you work on your remnant(s) please reach out to us.

These Wheatbelt NRM projects are supported by funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program.